Andrew Cuomo, due process hypocrite: Compare the tribunals under his campus sex assault law with the AG’s investigation

In 2015, after passage of the ”Enough Is Enough” law addressing campus sexual assault, Gov. Cuomo foresaw a cultural change for New York undergraduates. The law, he maintained, not only would require universities to adopt more complainant-friendly adjudication policies. It would marshal “the power of government to actually change the way society lives and how we treat one another.”

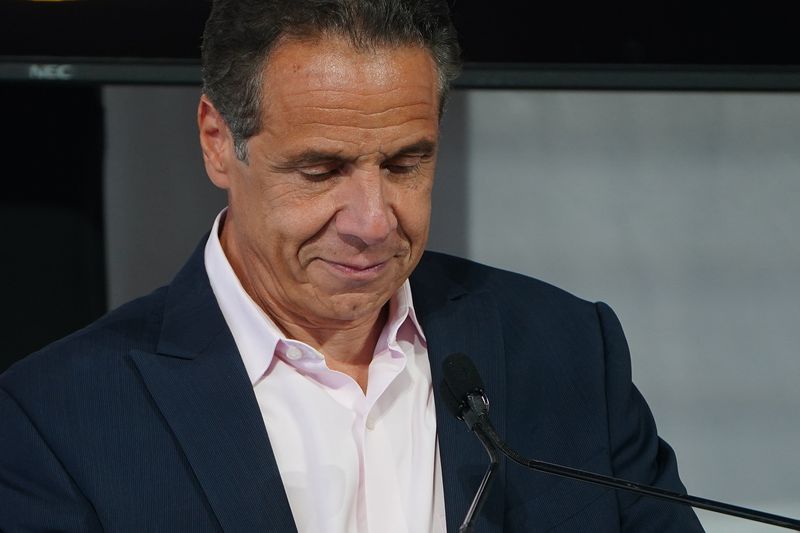

In light of the independent investigative report issued by the attorney general, Cuomo’s words seem like the musings of a man desperate to use public policy to obscure private misconduct. While the governor now portrays himself as the victim of a “biased” review process, his previous record makes it hard to take seriously a sudden concern with procedural fairness. Compared to the tribunals he imposed on the state’s college students, Cuomo has received more than enough due process.

Unlike the Cuomo of this week, in 2015 the governor was adamant on the need to protect complainants, even if it meant tilting procedures unfairly in their favor. As the Legislature considered his campus sexual assault measure, Cuomo hosted a screening of the victims’ rights film “The Hunting Ground,” for which his sister, Maria Cuomo Cole, was executive producer. The film, whose accuracy has come under withering criticism from journalists such as Emily Yoffe and Cathy Young, portrays campuses as dominated by predatory males enabled by timid Title IX administrators.

The Legislature overwhelmingly approved Cuomo’s bill, which requires a process “free from any suggestion that the reporting individual is at fault.” (If the allegation is false, of course, the reporting student is at fault.) The law also mandates an “affirmative consent” standard that shifts the burden of proof to the accused, and has schools place a mark on the transcript of students found guilty.

Despite its gender-neutral language, Cuomo portrayed the measure as solely protecting female students, who needed the power of his office to safeguard their opportunity for a college education. “It has to be an affirmative consent by the woman,” the governor asserted. He told male students, by contrast, “You’re not getting away with what you got away with before.”

Cuomo’s rehearsed rebuttal this week featured no discussion of “The Hunting Ground”or gubernatorial lectures to unidentified predatory male students. Instead, the governor maintained that the most serious claim against him, that he groped an aide, “never happened,” while suggesting unfair procedures tarnished the report’s other holdings.

Yet the state’s investigation gave Cuomo far more protections than accused students have had under his policies. He received full notice of the allegations, based on precisely defined state and federal statutes and investigated by figures independent of the attorney general’s office. He benefited from active legal representation and a meaningful chance to respond to the many claims against him. And if an impeachment trial occurs, he’ll have the right to cross-examine his accusers.

The contrast between some of Cuomo’s new positions and the outcome of cases involving New York college students charged under his policies is striking. For instance, Cuomo now demands an intent-based carve-out to the “affirmative consent” standard he formerly championed. Some of the actions detailed in the attorney general’s report, he claimed, were innocent gestures, because he intended “to put people at ease. I try to make them smile.” Contrast that to a case at SUNY-Purchase, where the university not only ignored the accused student’s intent, but also multiple actions by the complainant indicating consent. It took a state appellate court to set aside the university’s finding. One judge wondered if SUNY believed that the accused student could only satisfy Cuomo’s affirmative consent standard by “at every step along the way, [getting] her to sign a little waiver, or say something.”

In the Cuomo inquiry, a clear delineation of authority separated state officials from independent investigators Joon Kim and Anne Clark. Contrast that procedure to an infamous case at SUNY-Plattsburgh, where the Title IX coordinator investigated, served in a prosecutorial role during the accused student’s hearing, and (inaccurately) instructed the disciplinary panelists about the meaning of consent under the “Enough Is Enough” law.

Finally, even Cuomo couldn’t point to clear instances in which Kim and Clark had misrepresented evidence. Nor could he deny that he had a full opportunity to respond to the claims during the investigation itself. As one practitioner observed, it’s “amazing what detail, accuracy and reliability comes with investigative due process.” Those characteristics were in short supply in a case at SUNY-Albany, where a New York appellate court found that the university’s Title IX coordinator “admittedly altered the facts as reported to her” in a way that bolstered the accuser’s claim.

Cuomo has aggressively worked to undermine the rights of accused students in cases like the Purchase, Plattsburgh and Albany ones. If he applies his own standards to himself, he has no choice but to resign.