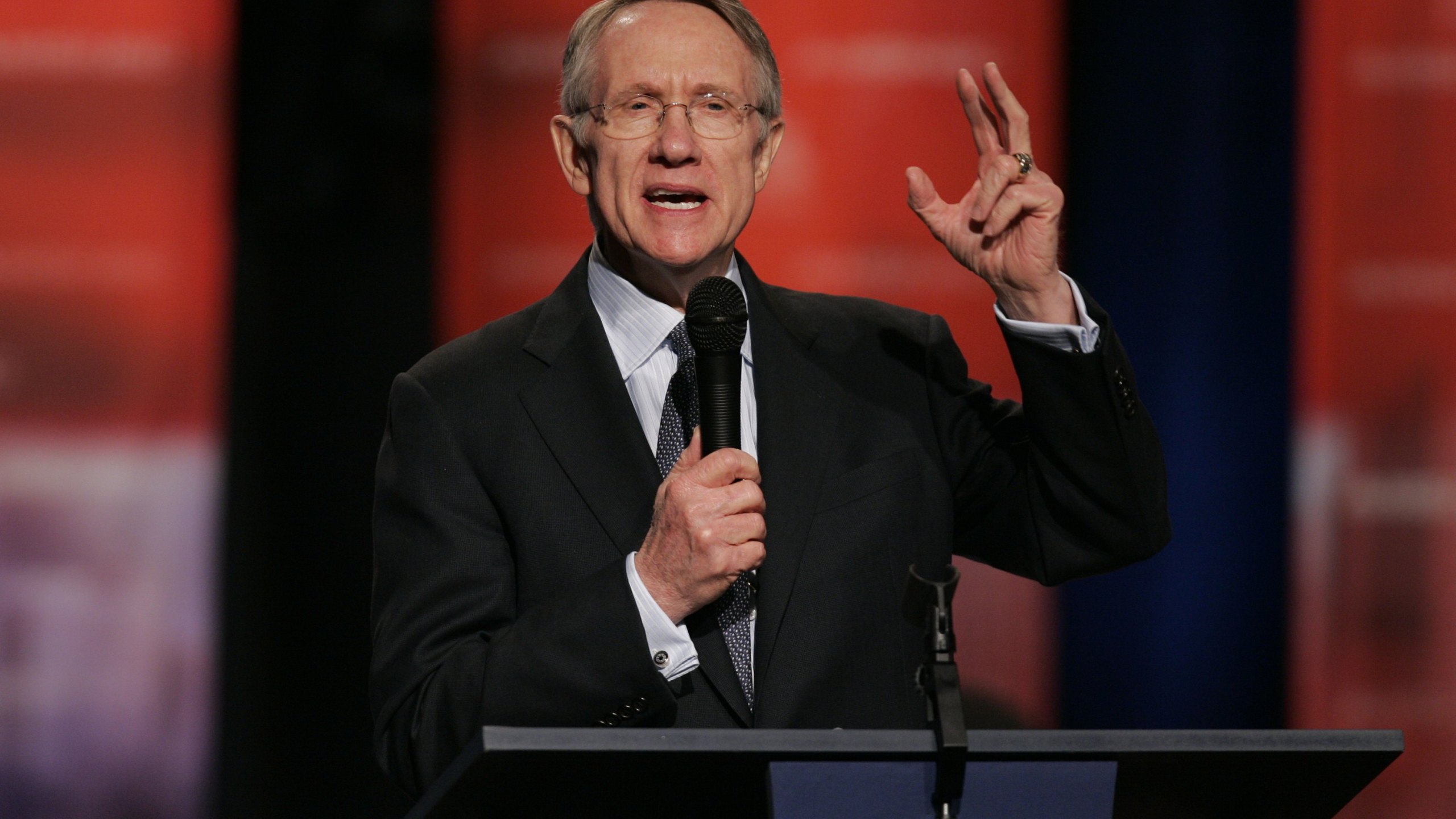

Harry Reid, political pugilist and longtime Senate majority leader, dies

Former Sen. Harry Reid (Nev.), one of the Senate’s longest-serving majority leaders and a Democrat who played a central role in enacting former President Obama’s biggest legislative accomplishments, died Tuesday at 82.

The death was announced by longtime political reporter Jon Ralston, who called Reid “probably the most important elected official in Nevada history.”

BREAKING: Harry Reid, probably the most important elected official in Nevada history, has died at 82.

My condolences to his family and friends.

— Jon Ralston (@RalstonReports) December 29, 2021

“Harry Reid was one of the most amazing individuals I’ve ever met,” Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) said in a statement. “He was my leader, my mentor, one of my dearest friends.”

Harry Reid was one of the most amazing individuals I’ve ever met

He never forgot where he came from and used those boxing instincts to fearlessly fight those who were hurting the poor & the middle class

He’s gone but will walk by the sides of many of us in the Senate every day pic.twitter.com/8T9PiD7vY4

— Chuck Schumer (@SenSchumer) December 29, 2021

Reid served as majority leader from 2006 to 2014 before retiring from politics in 2017 as one of the most influential and powerful Democratic leaders ever to serve in Washington.

He was elected Senate Democratic whip in 1998 and Senate Democratic leader in 2004, and became majority leader when Democrats took over the House and Senate at the height of public frustration with the Iraq War.

Reid, whose service as majority leader was surpassed only by former Sens. Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.) and Alben Barkley (D-Ky.), was not afraid to engage in open partisan warfare on the Senate floor, making him one of the chamber’s most divisive leaders in history.

He famously called George W. Bush, the sitting president, a “liar” and a “loser” and accused Mitt Romney, the GOP’s nominee for president in 2012, on the Senate floor of not paying his taxes.

He later apologized for calling Bush a loser but stuck by calling him a liar and never apologized for painting Romney as a tax cheat, even though PolitiFact rated the claim “Pants on Fire.”

Reid’s response was classic Reid. Terse and to the point.

“Romney didn’t win, did he?” he told CNN’s Dana Bash when asked whether he had any regrets.

Reid’s dogged effort to unify all 60 members of the Democratic caucus to pass the Affordable Care Act in 2009, the largest entitlement program passed since Medicare, ranks as the biggest legislative accomplishment of recent history.

To win over former Sen. Ben Nelson (D-Neb.), a pivotal moderate, Reid agreed to have the federal government to pay Nebraska’s share of the cost for expanding Medicaid, a deal that critics called the Cornhusker Kickback, and was later dropped.

Reid proclaimed it as victory that “affirmed the ability to live a healthy life in our great country is a right and not merely a privilege for the select few” and dedicated it to his friend Ted Kennedy, who had recently died.

His other signature victories were the passage of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in the depth of the Great Recession and, as the nation was beginning to recover, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act, which sought to rein in excesses that had nearly collapsed world financial markets.

Reid’s aggressive political style often evoked allusions to his record as an amateur boxer.

His breakthrough in politics came in 1970 when his mentor and high-school boxing coach Mike O’Callaghan, who went on to become a successful politician and run for governor, asked him to serve as his running mate.

In a Tuesday statement, Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak (D) said he was “heartbroken by the news” of Reid’s passing.

“To say Harry Reid was a giant doesn’t fully encapsulate all that he accomplished on behalf of the state of Nevada and for Nevada families; there will never be another leader quite like Senator Reid,” Sisolak said.

Reid’s life was a modern-day Horatio Alger story.

He grew up in Searchlight, Nev., an isolated mining town, where he learned to swim at the indoor pool of the local bordello and lived in a shack made of railroad ties soaked in creosote to keep the termites out.

When he left the Senate, his net worth was estimated in the millions of dollars.

He also left a political dynasty behind. His son Rory served as Clark County commissioner and ran for governor in 2010.

Reid worked in the Capitol as a police officer to pay for his studies at George Washington University’s law school, served four years as a member of the House and 30 years in the Senate.

He was elected the state’s lieutenant governor at age 31.

Reid was known in the Senate for hating to gab on the phone and often hung up on colleagues without saying goodbye, sometimes leaving them to talk at length to themselves.

He made up for it, however, by being a diligent student about what his colleagues needed and often delivered by putting in hours of legwork.

“I was always willing to do things that others were not willing to do,” he told The New York Times in a 2019 interview.

Democrats celebrated Reid’s career during his final month in office with star-studded farewell tribute in the Russell Building’s Kennedy Caucus Room, where President Biden praised him as a “man of your word” and declared that no majority leader in his memory had “a tougher job at a tougher time.”

Many Republicans, however, were happy to see Reid go.

Then Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.) angrily predicted in 2013 that Reid would be remembered as “the worst leader of the Senate ever” if he went ahead with a controversial rules change known as the nuclear option to make it easier to confirm Obama’s appellate court picks.

Undeterred, Reid went ahead with the unilateral procedural move in November of that year, lowering the bar for confirming executive branch and judicial nominees below the level of Supreme Court.

Breaking the Republican filibuster allowed Obama to fill three vacancies on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, the second most powerful court in the nation, and swing its majority to the left.

Reid later told The Hill in an interview that he kept the 60-vote hurdle for the Supreme Court out of deference to former Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.), an outspoken defender of women’s reproductive rights. Boxer, however, said in a follow-up interview that she did not remember any special arrangement with her leader.

Reid was also known during his tenure for keeping a tight grip on the Senate floor, protecting his vulnerable Democratic colleagues from taking tough votes by routinely filling the Senate’s amendment tree. But his tight leash on floor activity chafed colleagues in both parties who found it difficult to get their business considered in the chamber.

Former Sen. Mark Begich (D), a first-term senator from Alaska, came under criticism shortly before his reelection when it became known that he never received a roll-call vote on an amendment during his first 5 1/2 years in the Senate.

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) complained in June of 2014, a few months before Democrats lost their Senate majority, that he had “never been in a less productive time in my life than I am right now, in the United States Senate.”

Republicans promised that if they won back control, they would open up the floor to robust debate and frequent voting and while there have been some flashes of that, such as the immigration debate of February 2018, McConnell, who is now majority leader, has largely followed Reid’s example of keeping tight control over the floor.

Reid’s politics evolved during his time in Washington, a reflection of his job representing the entire Democratic caucus, which for much of his career was significantly more liberal than his home state of Nevada.

Early in his Senate career he said abortion should only be allowed in cases of rape or incest and voted against resolutions stating that Roe v. Wade, the landmark abortion rights case, had been correctly decided. For his last year in office, he had a 100 percent rating from NARAL Pro-Choice America.

He also changed his views on the Second Amendment. He accepted money from the National Rifle Association in the early nineties and once described himself as supporting the gun-rights group as “right down the line.”

Years later as majority leader he brought a gun-control package to the Senate floor in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting that would have expanded background checks and banned military-style assault weapons and high-capacity magazines.

Yet while Reid’s politics changed, he kept a sharp focus on his constituents back in Nevada and invoked his home state frequently, especially in the final years of his career after surviving a tough reelection in 2010, the year of the Tea Party revolution.

He made opposition to the nuclear waste repository in Yucca Mountain a signature issue and funneled back plenty of federal pork to Nevada as the chairman of the Senate Appropriations Energy and Water Subcommittee.

Republicans thought they had an excellent chance to knock off Reid, who had a dismal 38 percent approval rating — compared to a 54 percent disapproval rating — at the start of the 2010 cycle. But Reid was helped by the changing demographics of the state, which Obama won in the 2008 election.

Reid dodged a bullet when Tea Party favorite Sharron Angle won the Republican primary. His political team pummeled her for calling a fund helping the victims of the Gulf oil spill a “slush fund” and saying that rape victims should make lemons into lemonade if they become impregnated. He ended up winning reelection by a comfortable margin.

Reid survived an earlier political scare in 1998 when he barely won reelection over Republican John Ensign after a recount put him ahead by only 401 votes out of more than 400,000 cast.

Ensign went on to win election to the Senate in 2000 and Reid made an extra effort to cultivate a friendly and effective relationship with his home-state colleague. Reid’s goal was to both maximize what he could get done for Nevada but also undermine future GOP efforts to oust him from office.

Reid employed the same strategy of keeping your friends close but your enemies closer with Brian Sandoval, the Republican who later served as Nevada’s governor.

He recommended Sandoval to a federal judgeship in 2004, which kept the rising Republican star out of politics for four years until he quit the bench to reenter the fray and defeat Reid’s son Rory in the 2010 governor’s race.

Reid was a devotee of exercise and sometimes joked about his deputy, Schumer, spending more time on his cellphone and cutting deals in the Senate gym instead of working out.

He suffered a couple of injuries, however, that may have hastened his retirement.

Reid once gave himself a black eye on a jog when he fell after his hand slipped off a parked car he was using to stabilize himself while stretching.

He endured a much more serious injury in 2015 when an elastic band he was using in the bathroom snapped, sending him reeling into some cabinets. The accident left him with broken ribs and partially blinded.

Reid saw his time as leader was near an end after the 2014 midterm election when Republicans picked up nine seats and several centrists in his caucus, including Manchin and former Sens. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) and Heidi Heitkamp (D-N.D.), voted against him serving another term as Democratic leader.

He tapped Schumer to succeed him in May of 2015, leapfrogging his longtime whip, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.).

Reid underwent surgery to remove a tumor from his pancreas in May, an operation that left him frail and needing a walker.

In an interview earlier this year, Reid told Times reporter Mark Leibovich with his trademark bluntness, “As soon as you discover you have something on your pancreas, you’re dead.”